Kalamazoo Woman Perseveres Through Two Heart Attacks Caused by Uncommon Heart Condition

Jake Newby

| 5 min read

Jake Newby is a brand journalist for Blue Cross Blue...

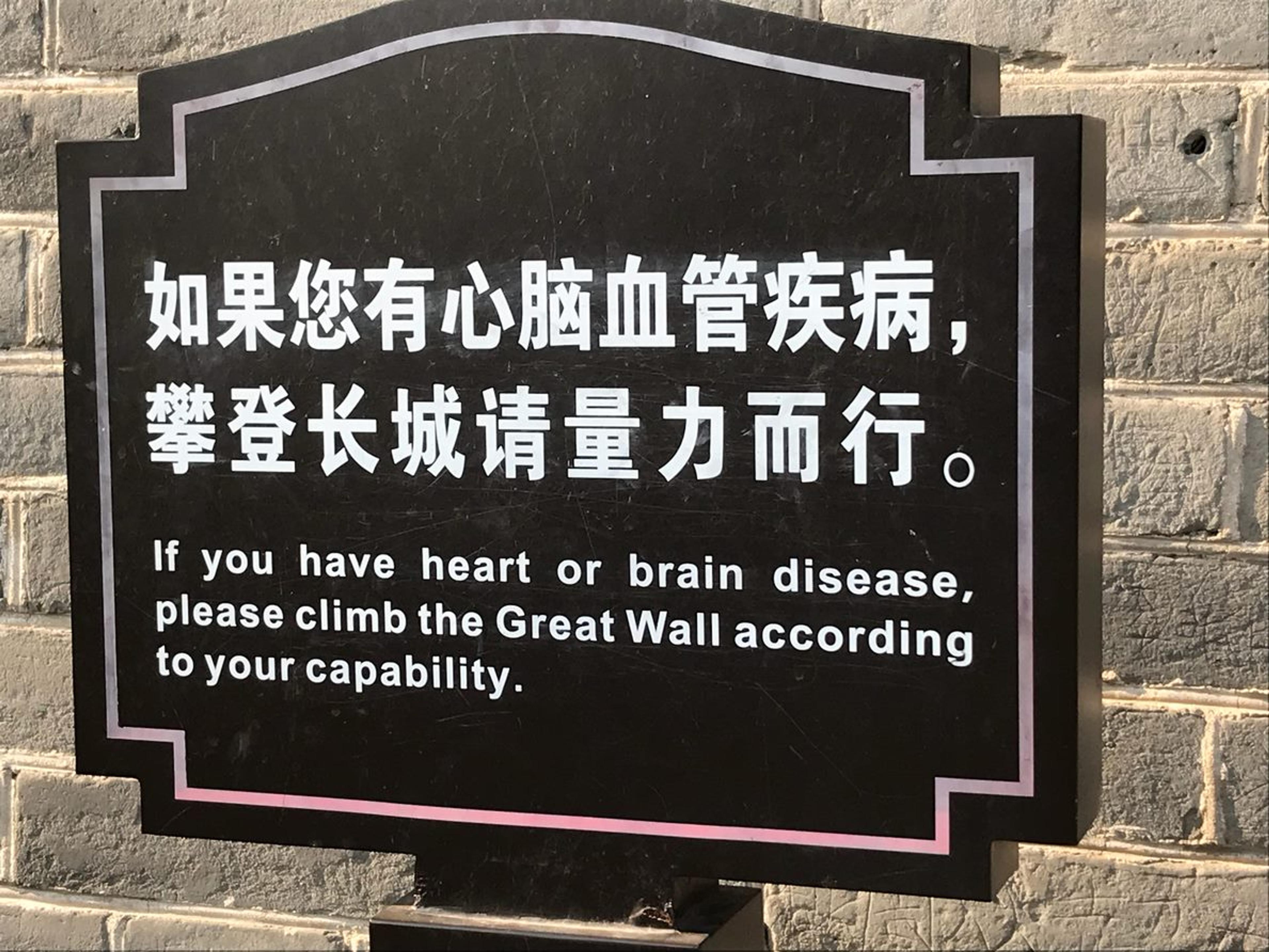

Doctors once told Kalamazoo’s Carrie Hamilton that it was unsafe for her to scale the stairs of her apartment complex because of her heart condition. Fast forward a handful of years later and she was standing at the top of the Great Wall of China.

Hamilton suffered her first heart attack out of nowhere, when she was just 38 years old. She said it felt like getting “hit by a bus.” It was sudden, it was physically painful, and it felt extremely random for someone who didn’t drink, smoke, or live with any preexisting health conditions.

“One of the physicians said my angiogram looked like it belonged to a typical 70-year-old woman and my doctor’s like, ‘Well no, she’s 38,’” Hamilton said. “It was just a very shocking and devastating diagnosis.”

Hamilton was diagnosed with a relatively obscure heart condition known as Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD). Doctors determined SCAD to be responsible for her heart attack.

“The first word of the diagnosis says it all: spontaneous,” she said. “It means that the interior layer of the arteries tears apart and creates a tissue plaque. And for me, that tissue plaque has gone on to create two heart attacks.”

More than 90% of SCAD patients are women, according to new research. Most people with SCAD are under the age of 65 and affected patients tend not to have typical risks for heart disease, such as smoking and obesity. As Hamilton processed her first heart attack, she sought support from fellow SCAD survivors online. She recalls being the 36th member of a group that now lives on Facebook and connects 6,200 members from across the world to each other.

Heart attack no. 2

Finding relatable support meant the world to Hamilton. But just as she was starting to turn a corner with her health, she suffered a second heart attack, less than 20 months after the first.

Severe emotional stress is a known risk factor for SCAD and it could have very well contributed to Hamilton’s second heart attack, which occurred just a week after the passing of her grandmother.

“I had similar symptoms. Rather than hitting me like a bus, this one hit me like a freight train this time,” Hamilton said. “That one happened at the stroke of midnight on my husband’s birthday. Before I could say “happy birthday, honey,” it was, “honey, this nitro(glycerin)’s not working. Honey, call 911. Honey, bring me a bucket.’”

This time, Hamilton flatlined in the cardiac catheterization lab, which is a specialized area in the hospital where doctors perform certain cardiac tests and procedures to treat heart conditions.

“They rushed me into emergency double bypass surgery,” she recalled. “They asked my husband if I drank or I smoke because they said trying to sew up my arteries was like trying to sew up mush. But no. I’m the epitome of the Adam Ant song, ‘Goody Two Shoes.’ ‘Goody Two Shoes, don’t drink, don’t smoke, what do you do?’ Well, I have heart attacks, apparently.”

Adjusting to life after two heart attacks

Hamilton faced a long, winding road to recovery after waking up from a week-long coma. She described herself as “emotionally numb” for 18 months.

“In those early days of SCAD, not a lot was known,” Hamilton said. “It probably wasn’t until I had my second heart attack that serious research got underway at the Mayo Clinic. But at the time, they told me I couldn’t lift anything that weighed 5 pounds – a gallon of milk weighs 8 pounds. I was told not to do stairs – we lived in a third-floor apartment. My husband and I were wavering on having a child at that time and they told me not to get pregnant. It was like, ‘OK, decision made.’”

That initial medical advice has largely been walked back as more information has surfaced on SCAD, which is why Hamilton was given clearance to climb structures much steeper and more physically demanding than the stairs outside of her apartment.

“With my doctor’s approval, I have also climbed to the top of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris,” she added.

Hamilton does still have lifting restrictions limited to a 20-pound maximum per arm. She’s also on full disability because of the amount of scar tissue and damage to her heart. She has an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) because of all that scar tissue and damage, which makes her susceptible to sudden cardiac arrest.

Finding support and learning a crucial skill

Hamilton’s heart is damaged, but her spirit and attitude are as strong as they’ve ever been.

“I’d never wish a heart attack on my worst enemy, I don’t recommend it, they’re not pain-free,” she said with a laugh. “But I try to find silver linings. After my second one, I really struggled to find those, but I did. I was able to bring a support group to Kalamazoo, and right now we’re in the process of starting it back up, post COVID. That’s been monumental for all women in the area who are at-risk for heart disease.”

Between the in-person and online support groups she’s joined, Hamilton has found sources of support and relatability that she can’t find elsewhere.

“My husband is extremely supportive … I can go home and talk to him, and he can give me the hugs and all the support, and I’m grateful to have that,” she said. “But talking with other women who have been there is a game-changer. It’s so much easier to not feel so alone.”

Support from her husband and fellow SCAD survivors has been a boon to Hamilton’s mental and emotional health. Physically, she said the importance of knowing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) have resonated with her in a major way.

“Fortunately for me, I was in the cath lab receiving CPR from trained professionals when I needed it, but most people who need it are not in a hospital,” she said. “Learning CPR is very easy now. My advice to anybody is to learn it. You never know whose life you’re going to save. I’ve talked to so many women whose husbands were there, caught them as they fell into cardiac arrest, performed CPR, and that’s why they’re here today.”

Photo credit: Carrie Hamilton