University of Michigan Professor Examines Why Black Women Are Not Returning for Follow-up Cervical Cancer Screenings and Identifies Self-Screening as a Solution

Jake Newby

| 6 min read

Jake Newby is a brand journalist for Blue Cross Blue...

Cervical cancer screenings are unlike any other cancer screening in that test results don’t provide cancer clarity right away. In some cases, it can take repeated screenings and abnormality discoveries to determine a pre-cancer diagnosis, a process that confuses some patients and makes them frustrated enough to skip follow-up visits.

A University of Michigan (UM) physician and professor found this to be especially true among Black women, who are 41% more likely to develop cervical cancer than non-Hispanic white women.

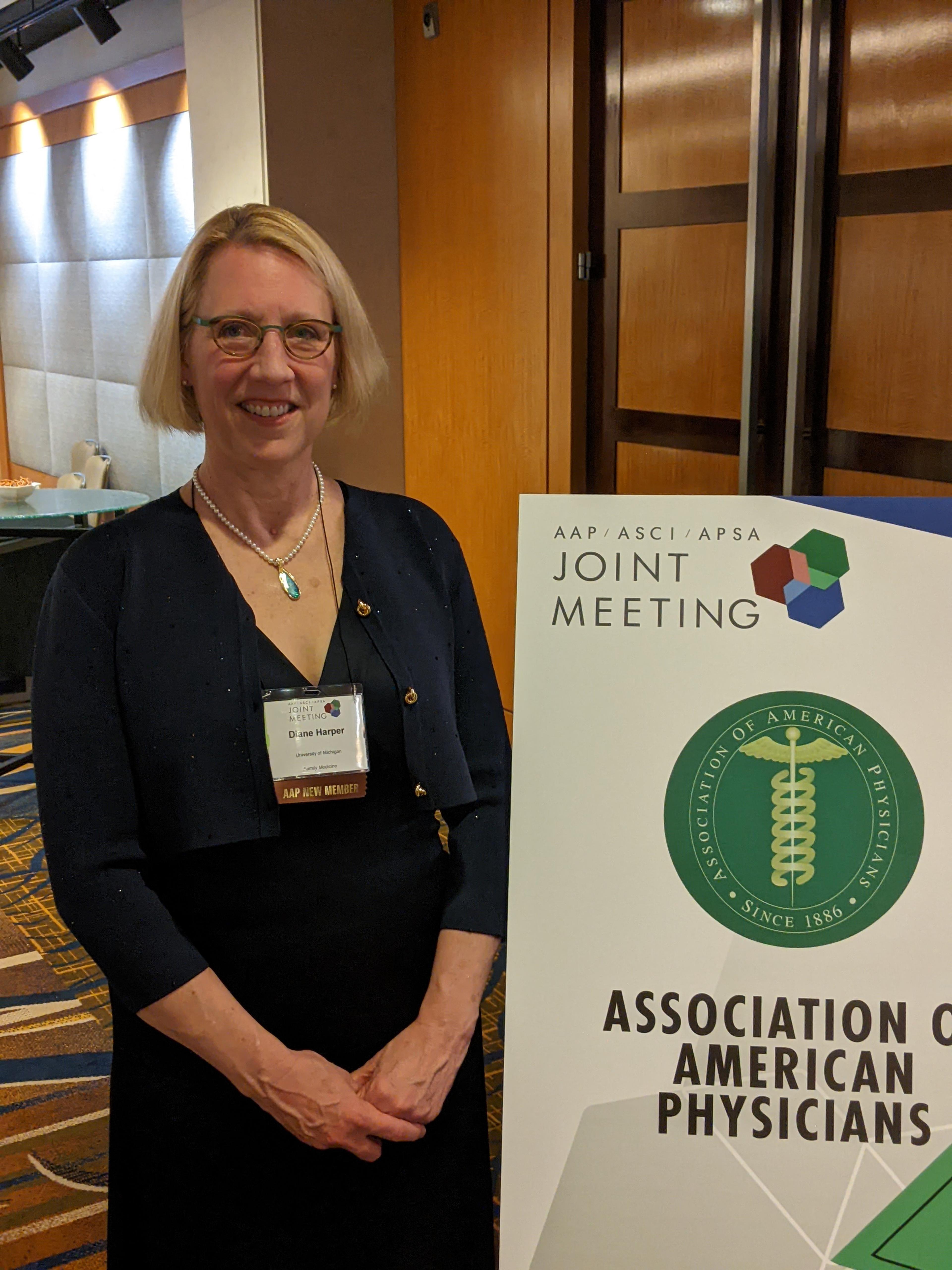

UM Professor Dr. Diane Harper, an internationally recognized family physician and clinical research expert in HPV-associated diseases, has dedicated much of her career to cervical cancer prevention. During the past year, with the help of the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) Foundation’s $10,000 Physician Investigator Research Award, Harper and the talented research team she has mentored not only spent time conducting qualitative interviews to learn more about why Black women aren’t returning for crucial follow-up appointments, she’s designing the framework to find a solution.

“With cervical cancer, so many people don’t understand that when they get the results of their cervical cancer screen back, it’s not a cancer or no-cancer answer,” Harper said.

Cervical cancer results indicate whether the person screened is infected by the Human papillomavirus (HPV) that causes cervical cancer. If a person is infected with HPV, the results examine whether the virus has been in their system long enough to cause any changes that physicians can find and eliminate, though the HPV virus itself is incurable. The gray-area nature of this exam can dissuade some people from returning for a follow-up visit. Harper said other factors contribute as well, such as the colposcopy diagnostic procedure, which require the use of speculums and takes biopsies of the cervix. These are tools used to widen the vaginal walls and allow physicians to inspect the cervix and vagina for abnormalities.

“Colposcopies involves putting women in a very uncomfortable position, physically see, for close to 15 minutes,” Harper said. “That’s one of the things we heard from women, was there was emotional distress. They were concerned, asking, ‘is this cancer or not cancer and what is this exam I have to go through?’ I think the misunderstanding of what the results are.”

Another issue, Harper said, is that much of the screening appointments are spent gathering the specimen and very little time is spent educating patients. Finally, there’s a fatigue factor.

“If you’re HPV positive for the highest-risk HPV types, which are 16 or 18, we refer you immediately for a colposcopy,” she explained. “If you are HPV positive for one of the 12 other high-risk types, you have to have a cytology test, which then determines if you need a colposcopy. There is a group of women who are continually positive for HPV, whose cytology is just a little bit abnormal, so they continually get stuck in this cycle where they are referred to a colposcopy and told to have a follow-up exam yearly. The reason this is a problem is, women are saying ‘yeah, it’s abnormal again, it’s been abnormal the last five times. I don’t really care; I don’t want to go through this anymore.’ But those are exactly the women who are most susceptible to developing cervical cancer and need follow-up care the most.”

Harper added this trend can be dangerous because it takes 15 years for an HPV infection to evolve into cervical cancer.

“While you are being tested repeatedly, and your HPV test is still positive, but (doctors) aren’t finding anything concerning during colposcopies, you are still putting in time for that HPV to progress into a cervical cancer precursor,” she said. “But as the patient you’re thinking, ‘nothing has been wrong for five years in a row, why do I need to keep coming back? It’s uncomfortable, it’s not covered by insurance. I have to pay an out-of-pocket cost to get one.’ Women lose interest.”

At-home cervical screening and self-collection as a solution

The BCBSM Foundation grant has helped UM identify these barriers to follow-up screenings by talking to women. The next step, Harper said, is to create educational materials for patients and physicians that revolve around incorporating self-screening as the primary method of cancer screening within as many health care systems as possible. This solution not only stands to save patients time and money, but it can also save lives.

“Self-screening becoming the standard here like it is in Europe would make it not so onerous for women to keep coming in for speculum exam after speculum exam,” Harper said.

She said by the spring at UM facilities, any woman of screening-eligible age who needs a cervical cancer screening will have the option to have a speculum exam or conduct self-sampling, with a push toward self-sampling as the most efficient way to screen women for cervical cancer.

“This is incredibly exciting,” she said. “It’s moving women into the 21st century.”

“Cervical cancer already disproportionately affects Black women, so when they become discouraged enough during screenings to avoid follow-up visits, the issue is compounded,” said BCBSM Foundation CEO and Executive Director Audrey Harvey. “Dr. Harper and her staff are doing the research needed to find out what women would like to see in terms of meaningful, systemic changes.”

Cervical cancer carries with it a heavy stigma. There’s a stereotype that women diagnosed with it are sexually promiscuous. In addition to the complicated screening process, it’s a cancer that women can’t physically, because unlike with male genitalia, any lesions or physical abnormalities are internal. For these reasons and more, Harper is passionate about educating women and helping them prevent or overcome cervical cancer.

“Women don’t really own the disease or understand it,” she said. “The horrible things I’ve heard from women about having to undergo pelvic exams and speculum exams, just undressing. The mental and physical preparation a woman goes through before those exams is pretty amazing. Anything I can do to help this experience be less painful, to not remind them of any sexual trauma or bad experiences they’ve had from relationships, will ultimately help women in the U.S. become healthier.

“We now have the tools,” Harper added. “Through my work at Dartmouth Medical School, I led the clinical trials to bring HPV vaccination to the United States. My Michigan research team is now bringing self-sampling so we can get away from the speculum exam. We are now actively working on trying to find a cure for HPV. This will all help us be able to prevent a cancer that we should and have every right to prevent.”

Click here to learn more about the BCBSM Foundation’s Physician Investigator Research Award Program, including the grant application process, eligibility requirements and more.

More Foundation stories:

- BCBSM Foundation awards $116,000 to Michigan Organizations Promoting Child Wellbeing and Preventing Abuse and Neglect Before it Happens

- Coffective Expands Warm Referral Network, Provides Crucial Maternal Support with Help from BCBSM Foundation

- Detroit’s Strategic Community Solutions Combats Caregiver Burnout with Innovative ‘Rest & Recharge + Helping Hands’ Program for Southeast Michigan Caregivers

Photo Credit: University of Michigan